|

Georgeville Historical Society / Societé d'histoire de Georgeville

|

|||||||||||

|

THE LOST VILLAGE OF MAGOON'S POINT The following edited text is from a presentation delivered by historian and GHS director Stephen Moore at the Annual General Meeting of the Georgeville Historical Society, July 16, 1994. Stephen was introduced by his great aunt, Adelaide Atkin, a fellow director.

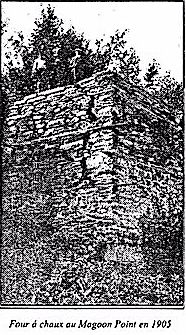

Now I must say at the outset that I have no pretensions to being an expert on the subject for I'm sure that there are a number of people in the audience today who have either lived or worked on the Point, or had relatives or friends who did in years gone by and are thus, no doubt, more familiar with the Point than I am. Rather, I am simply someone who has always been interested in the Point, my ancestors having resided in this locality over a century ago. And perhaps moreover, I stand before you today as a representative of the Board of Directors, the members of which join me in the hope that I will be able to jog the memory of some, and possibly enlighten others, as to the history of this one–time community that prospered in the shadow of Georgeville and Fitch Bay. For the younger members of the audience and those who are newcomers to Stanstead Township, the name Magoon's Point has come to represent the large promontory four miles to the south, that dominant point of land that delineates the main body of Lake Memphremagog from the long arm of Fitch Bay. If I were to step outside, for example, and approach some of the teenagers down in the village, and ask them to define and locate Magoon's Point, they would all inevitably point in the general direction of the Point and begin to mumble how it is this large, wild track of land along the lakeshore, that is heavily wooded, sparsely populated, and somewhat inaccessible. And they would be quite accurate in their description, for that is the image that many people have come to visualize in their minds when they hear the name Magoon's Point: a distinct geographical section of land. The name, as such, has become part of the local vernacular, as familiar as other local geographical features associated with the township, the Narrows and Brown's Hill, to mention but two other examples. Now, for the older members of the audience, and I include myself in this category, and those of us who are interested in matters of a historical nature, the name Magoon's Point also represents the unique and distinct community that once existed down on the Point over a hundred years ago. Upon investigating the history of Magoon's Point, researchers such as myself face an up–hill battle. Unfortunately, we are not blessed with a great wealth of information about the community. Compared to Georgeville, the base of knowledge is practically non–existent. There are for example, no actual photographs of the village proper. The community itself was but a small hamlet at the best of times, and despite what appears in the newsletter, the population probably never rose above one to two hundred individuals. This may account for the disparity with regard to archival material between the two communities. Its diminutive size, however, was not unique. During the 1800s the county of Stanstead had as many as 36 separate communities; the township, as many as 13. And please note that whenever I mention the township of Stanstead today, I will be referring to its primitive territorial limits that included the present day municipalities of Ogden and Stanstead–East. Many of the communities were small villages, tiny hamlets or in some cases, mere crossroads. The names of many of these communities are familiar to most of you today, even such places as Apple Grove and Griffin's Corner, which retain few of the vestiges of village life that were so evident in previous years. Magoon's Point, therefore, was simply one of many small communities that characterized the nineteenth century landscape. Because of its size and location vis a vis the neighboring communities of Georgeville and Fitch Bay, Magoon's Point lacked much of the infrastructure that was established in these other two villages. It did not have any artisans to speak of or religious institutions, but it did have a post office, a small store, a one–room schoolhouse, a two–story boarding house, various private residences and a cemetery. It also a direct link to the outside world via its telephone connection to the Rider system based in Fitch Bay. At the moment nothing is known of the village's origins. Its name, we may assume, like the Point itself, is derived from the Magoon family who were among the earliest settlers. Indeed, the village's 'raison d'etre' is likely attributable to the Magoon family's lime manufacturing endeavors that were in operation as early as the 1820s. The labour–intensive production of lime, served as a local source of employment and the impetus that led to the establishment of the tiny community. The importance of this economic activity was reflected in the layout of the village that tended to coincide with the two principal facets of the operation, namely, the process of extraction and the process of refinement. We find, therefore, that the various components of the village were clustered about the two sites associated with these two processes, specifically, the quarries and the kilns. It is impossible to over emphasize the importance of the lime business to the community of Magoon's Point. It was the heart and soul of the village. The business evolved during the 1800s because the raw product, limestone, was discovered in an outcrop on the Point and there was at the time, as there is now, a market for the lime that could be derived from it. There are a number of deposits of limestone in the Memphremagog area, notably north and south of Georgeville, though the purity of the stone as measured by the percentage of calcium content, was notably higher on the Point than other areas surrounding Georgeville. A series of analyses undertaken sometime after the cessation of operations in this region indicated that the rates of purity on the Merriman farm north of Georgeville, as well as two separate locations on MacPherson's Bay, tested at 85, 88 and 73 percent calcium respectively. These percentages compared to a rate of 92 for Magoon's Point. This tends to suggest that the Magoon family enjoyed the most favourable deposit in the township that they were only too happy to exploit. The limestone on the Point was revealed in a series of outcrops above the road. Here as many as three separate quarries were established where the limestone, imbedded in upward–thrusting layers, was extracted. The raw ore was then transported by wagon down to the lakeshore where it was either shipped in its origin state or refined on the lakeshore in one of the family's limekilns. Because of its high quality, a demand existed for the limestone that was excavated on the Point. During certain periods, large quantities of the ore were shipped to other local kilns, including one situated at Newport. During 1865, for example, an exporter by the name Putnam & Company shipped nearly 10,000 barrels (9980) of 'lime rock' or limestone across the line, all of which originated from the quarries on Magoon's Point. The wholesale exportation of raw material that characterized the activities of 1865, however, appear to be an anomaly compared to operations in other years. As a generality, most of the limestone, is believed to have been converted on site. As in the case of most primary industries, the high bulk/low value ratio of the raw material tended to favor this option. In layman's terms, the family was quick to realize that more profit could be derived by doing its own refining of the valuable resource at hand. As a result, a number of kilns were constructed over the years by various family members. The actual process was not complicated. The kilns consisted of two compartments, the upper encasing the limestone and the lower in which high temperatures were generated from hardwood fires. It was simply a matter of heating the limestone sufficiently enough as to cause the ore to crumble into a powder–like consistency. Devoid of the carbonic acids that were expelled through the 'burning' process, the residue that was produced was known as lime. An analogy may be made to the more familiar process of making maple syrup that is carried on today. The finished product was then packed in barrels and distributed throughout the countryside. The lakeside kilns reduced the amount of handling as the barrels were loaded directly onto barges, which in turn, were towed up or down the lake by one or more of the various steamers that plied the waters of Memphremagog. As an end product, the lime produced was a highly valuable commodity. By spreading it over their fields, local farmers could counteract the acidic tendencies of Eastern Townships' farmland. In essence, the Magoon family had a ready–made market. Area farmers had the option of buying their required quantities of lime direct from the kiln site or from one of the family's agents such as the Rider brothers of Fitch Bay. In addition to local markets, there was also an American demand for lime. We are not sure why, but the level of lime exports fluctuated wildly, ranging from a few hundred barrels in one year to as many as 6-7000 one year later. Fluctuations to this extreme suggest a degree of unreliability with regard to the consistency of kiln owners to operate on a continuous basis. To give you an idea of the scale of operations undertaken by the family, I would like to provide you with some data gleaned from the 1871 census as it applies to Aaron Magoon. In 1871 Aaron had $8000 invested in fixed capital, $7000 in operating capital. This was a great deal of money during this period. To give you some perspective, a sum of $2–3000 would fetch you a sizable farm complete with livestock and farm implements. Aaron operated nine months of the year, he employed 10 men and paid out wages amounting to $2350. To heat his kiln he used 1000 cords of firewood. Who among us today would not like to have a supply like that on hand to keep the woodstove going all winter – quite a few winters by my rate of usage! In all, Aaron produced 45,000 barrels of lime. The value of his raw material was set at $200, his finished product, $10,000. That's what businessmen mean when they refer to the term 'value added'. By any standard, the lime manufacturing business was a vital stimulus to the local economy. Indeed, in 1871 it was the largest industrial operation in the township in terms of capital invested and number of employees, discounting the factory operations in Stanstead-Rock Island. In terms of capital invested, the Magoon limekiln operation was in a league of its own. It even outdistanced all the various saw and gristmill operations in the township, not to mention all the local artisans and merchants. In addition to lime, the Magoon family also manufactured firebricks in the family kilns on the Point. Whether or not the same kiln or kilns were employed as were used for the manufacture of lime is unclear. In fact, very little is known about the whole operation. We do know, however, that in 1865, an unspecified member of the family exported 25,500 firebricks to the United States, the value of which amounted to only $118. In an age when brick production measured in the hundreds of thousands, it would appear that the manufacture of firebricks was merely a sideline activity to the primary production of lime. In addition to limestone, the residents of Magoon's Point were also able to exploit other mineral resources. During this same time period Aaron Magoon sold off quarry rights pertaining to oilstone, or what is more commonly known as whetstone, to a Massachusetts businessman. The transaction was later rescinded though when Aaron reacquired the rights and we are thus unsure as to how much extraction was actually carried on involving this particular resource. As well, on the western flank of the Point, a deposit of granite was discovered on the northern extremity of what is referred to in my family as 'the basin'. In comparison to the limestone quarries on the opposite side of the Point, the excavation of granite was a very minor operation. On the farm owned by my great-great-great grandfather, William Brevoort, granite was extracted from the steep shoreline by Nathan Beach, the well–known Georgeville contractor and entrepreneur. During the 1880s, Beach would barge the granite down the lake to be employed in the construction of, it may be assumed, building foundations. Unfortunately, nothing else is known of the operation, and judged by the scarcity of references to it, it's likely that the granite enterprise was short–lived. Now, before I leave the topic of mineral deposits, you might be interested to know that Magoon's Point is characterized by a number of different geological zones; that it is a rather complex area geologically speaking. This will explain the diversity of rock formations that in addition to the limestone, whetstone and granite deposits already discussed, and which I might add, span the broad spectrum of geological formations, also includes such outcrops as slate and shale in the MacPherson's Bay area. Of perhaps greater interest, though, is the fact that Magoon's Point lies directly on top of a major geological fault line that extends northeasterly up the length of Fitch Bay to Lake Massawippi and beyond to the Stoke Mountain range.

So please be forewarned – that if at some point in my talk this afternoon, the ground begins to rumble, the building starts to shake and you see me run out the door and up the road towards Magog, now you'll Despite all that I have just said about the lime industry, it was not the main preoccupation of most residents of Magoon's Point. Most residents were farmers, first and foremost. Even Aaron Magoon with his limekiln enterprise, also ran a sizeable farming operation. Sandwiched in between the high mountainous ridges to the northwest and southeast, the agricultural valley of Magoon's Point was characterized by a downward–sloping landscape that enjoyed the favourable orientation of a full southern exposure. The nature of farming on the Point was typical of the region as a whole. It was not the diversified approach of modern–day agriculture but mixed farming in its truest form. Most farms, for example, were self-sufficient with a broad variety of crops grown and livestock raised. As individual agricultural data records reveal, each farmer grew a healthy mix of wheat, barley, oats, beans, corn, potatoes and similar items while harvesting a sufficient supply of apples, honey, maple sugar and hay to support family members and livestock throughout the year. The selection of livestock was balanced to supply meat and dairy products for the table, wool for apparel and beasts of burden for work and transportation. It was after all, an era of home–grown/home–butchered food stuff and home–made clothing/linen. It was an age of subsistence farming tempered by sufficient cash crops as to warrant occasional staple necessities and longed–for luxuries. The farms below the cross–road (i.e. the road that goes from Brian Kay's over to Addie's) at the time of the 1871 census were typical of the overall township in terms of size, falling within the 50 to 300 acre range. And the average size of farms in this sector also fell within the average norms for the township, somewhat higher, if anything. Within the mix of farming pursuits, some farmers favored dairy husbandry while others tended to raise sheep, depending upon individual preferences. Regardless of the type of livestock raised, most people today would not believe the level to which farm acreage was 'improved' during the 1800s. Most people today would not recognize the nineteenth century agricultural landscape. As a somewhat noted photograph of Magoon's Point clearly indicates, a high percentage of land was devoted to crop cultivation or pastureland. The level of deforestation is barely comprehensible in today's age of tree farms and abandoned farm acreage. As the photograph suggests, most of the visible land on the Point was devoid of forest acreage. Not that this was abnormal, for the local landscape mirrored that of farmland throughout the county and the Townships as a whole. It is simply in such stark contrast to the present day reality and the image that most of us have of Magoon's Point. And by examining once again some of the statistics contained in the 1871 census, it is apparent that all this 'improved' farmland did not go to waste. What I would refer to as 'the' Magoon's Point farm', for example, was one of the most productive farms in the whole township. At 270 acres it was the largest farm on the Point, capable of supporting a herd of 25 milking cows, the second largest (actually tied for second) such herd in Stanstead Township. The farm at the time was owned by my great-grandfather, William Brevoort, the same individual I mentioned previously. Today a herd of 25 cattle seems unimpressive. However, consider that at the time, the average number of milch cows owned was merely 4.3. Surpassing this meager average were Wilder and Aaron Magoon, Thomas Bertrand and Thadeus Blake, all of whom had herds in the double-digit range. And not far away, up in the Merrill neighborhood, was William Brevoort's father Hiram whose herd of 23 ranked tied for 4th in the township. Not bad when one considers that discounting small hobby farms of less than 10 acres, there were over 500 farms in the township during this period. One of the primary objectives of those farmers with large herds was the production of butter. Throughout this period there was a high demand for butter especially with regard to external markets beyond the limits of the Townships. Butter was shipped both to Montreal and across the border, notably to the Boston area. While domestic use accounted for the lower ranges of butter production of 100–300 pounds, the larger farm herds were obviously destined to compete in the foreign markets, with production levels ranging from 700–1800 pounds. The average production for the township in 1871 was only 386 pounds and seven of the farms on the Point thoroughly surpassed this mark, falling within the latter range that I just mentioned. Surpassing everyone, however, was my great grandfather on the Magoon's Point farm who produced just under 4000 pounds, the most by far of any farmer in Stanstead Township. His closest competitor accounted for only 2800 pounds. Not to be outdone, however, were some of my great grandfather's neighbours. Thadeus Blake tied with two others for the position of 4th largest producer of butter, while Wilder and Aaron Magoon ranked 10th, tied also with two other farmers. These rankings are indeed remarkable considering there were over 560 producers in 1871. To capitalize on this market the Rider brothers of Fitch Bay attempted to organize a local co–operative so that local production could be sold in bulk. Though they were initially unsuccessful, in later years they were able to operate a collection and distribution system, which was managed through their general store. The Riders leased various steam tugs and barges, which circumnavigated the shoreline. Based upon the facts and figures that I just rhymed off for you, it would appear that the most important stop on their collection route was the dock or docks on Magoon's Point. Just as a side note, you might be interested to know that the Riders continually hounded the local municipal council to have the Narrows bridge raised. Its low clearance, you see, prevented steamships from accessing the upper reaches of Fitch Bay and thus precluded the village of Fitch Bay from ever becoming a port on the lake. This infuriated the Riders to no end since it meant that all the products that they dealt with, from the lime and butter produced on the Point as well as their own wood products manufactured in their various mills, had to be loaded and/or unloaded at the Narrows bridge. This was a major inconvenience and cost consideration that despite their efforts, could not be alleviated. After the turn of the century, local farmers really stepped up operations by involving themselves in various creamery schemes. The creameries, which were managed on a co–operative basis, removed the drudgery of home churning and gave the whole business a more professional air. The farmers of Magoon's Point were first served by the creamery in Fitch Bay which after 1903 was owned by the Rider family. About the time of the First World War this creamery sold out to the Griffin Creamery Association, which involved many local farmers. Unfortunately this operation went bankrupt within a few years and a number of farmers from the Point were affected financially, some like my great grandfather, George Atkin, quite severely. But that's another story. Of course, the farms on the Point were not always so productive, the neighbourhood so advanced. When John Boynton's ancestors, the Christies, acquired the Magoon's Point farm during the 1830s, it was a far cry from the productive operation that my great grandfather was able to exploit in later years. I would like to read you an excerpt from a manuscript written by Penelope Riedell, daughter of John Christie, supporting this assessment: "My father found (that) his Derby farm would not produce enough to keep his growing family as he wished them to live. And as farms on the Canad(ian) side of the 'Line' were cheaper, he looked around in the township of Stanstead. Mr. Colin Munroe, a (Scotsman who accompanied) our folks across the ocean, had bought a farm in the western part of Stanstead and sent word to have father come and buy near(by) as a large farm was for sale cheap. It was in the winter (that) my father bought in a neighbourhood called Magoon's Point. It was a winter of deep snows and fences were buried, and rough and rocky fields were very smoothly covered by their coating of snow. The shrewd seller knew that the snow was (to his advantage) and he dwelt on the extensive meadows and rich soils buried so deep. The purchase was made and in (the month of) March, 1837 we were settled in Canada." "As the spring weather advanced, the young folks in the family (rejoiced at the sight) and novelty of beautiful Lake Memphremagog which bordered two sides of the farm, the large extent of woods where the maple sugar was made, the rather thrifty apple orchard and the soft clear spring water running by the door." "I think father and mother were less satisfied. There were many drawbacks. We were far from church and market. Our neighbours were not all they desired – few of them religious and some quite immoral – and the schools were not (as) good as in Vermont. However, believing that the change had been made under Divine guidance, our parents tried to make the best of their surroundings." My apologies to John for a little editing for the sake of clarity. The moral of the story, I guess, is never buy property in the wintertime. It kind of makes you wonder just who these questionable neighbours were that Penelope alluded to! It couldn't have been any of my family for my ancestors did not move onto the Point until the 1860s. Besides, those disparaging accolades would only apply to some of my current relatives! Despite their initial disappointments, the Christie family nevertheless rose to the occasion and through hard work and perseverance, turned the farm into one of the most successful farming operations around. It's to their credit that my own family was able to prosper in later decades. If I may, I would like now to return to the subject of the actual village and describe to you some of the facilities that characterized it. First, there was the boarding house. Almost nothing is known about it except that apparently it was a two–storey building on the upper side of the road, opposite the cemetery and in the foreground of the quarries. It is believed that some of the employees from the quarries and/or kilns resided here. Next is the post office, the location of which is uncertain. We do know, however, that it was through the efforts of John Christie that the post office was established on the Point. This was an important achievement for not only did it make postal arrangements possible at the local level, it also signified a level of recognition on the part of the federal government. It put Magoon's Point on the map, so to speak. Mr. Christie served as postmaster from the inception of the office until 1869 when he sold the Magoon's Point farm and removed to Apple Grove. He was succeeded by Aaron Magoon who served during the 1870s and possibly the 1880s as well. He in turn, was followed by my great grandfather William Brevoort who was the postmaster for most of the 1890s, serving until 1902 when he resigned. For a period Aaron and my great grandfather alternated back and forth, perhaps in response to the direction of the prevailing political wind. In Fitch Bay, for example, the post office was known to have been literally carted back and forth in a wheelbarrow with each new change in government. It seems the qualifications for the position of postmaster had more to do with political affiliations than individual abilities. On display this afternoon, is the actual post office desk employed by my great grandfather down on the Point, and used possibly by some of the other postmasters as well. We even have a copy of the postal mark used to stamp letters and other related mail, showing the name in clear detail. With the resignation of my great grandfather in 1902, the role of postmaster was assumed by George Boynton and the office transferred to the Boynton farmhouse, up near where the Elephant Barn stands today. This was a significant blow to the community and perhaps a harbinger of events yet to unfold. Across the road from the boarding house was the village's cemetery. Set back from the main road a few hundred feet, the cemetery borders the roadway that leads to the lake. It is rather an old cemetery, with burial inscriptions dating back to the 1820s. Based on the information recorded from headstones at various times, it would be perhaps more appropriate to refer to the cemetery as the Magoon family plot as most of the people buried there appear to have been members of the Magoon family. Regardless of who was interred there, a more idyllic setting, with the lakeshore as a backdrop, could not have been found. Which brings us to the school. Built up on the hillside property of the old Simm farm, the small, one–room schoolhouse was a classic rendition of rural education. It is not known when the school was originally built but it at least predates the 1880s based upon its appearance in the Belden Atlas of 1881. It is believed to be the second one built, the earlier version having been situated on the western side of the village. The school operated for a number of decades, serving the school–age population of Magoon's Point as late as the period following the First World War. Eventually the school was torn down after which the local children were bused, and I use the term 'bused' loosely, either to the Merrill schoolhouse up on the Georgeville to Narrows road or the Boynton schoolhouse up by the Elephant Barn. Apart from the village itself, Magoon's Point was also well known during this period for the activity that took place right on the Point. In 1880 my great grandfather leased for a term of 99 years, the extreme seven and a half acres to the Connecticut & Passumpsic Rivers Railroad. The railroad in turn converted this small plot of land into a recreational retreat known as Bayview Park. With its panoramic views of the lake, the Park became a popular location for railway patrons. This was the golden age of tourism on Lake Memphremagog, a period when large, commodious hotels dotted the landscape from one end of the lake to the other. Not small country inns mind you, but huge resorts that included the Memphremagog House at Newport, the Mountain House at the base of Owl's Head, the Camperdown right here in Georgeville and the Park House in Magog. These were large edifices with guest rooms numbering as high as 500 respectively. It was an age when the railroad was involved in every facet of the tourist industry, including transportation, accommodation and entertainment. The railroad, for example, owned the railway transportation system, two of the major hotels, the Memphremagog House and the Mountain House, the lake steamer the 'Lady of the Lake' and finally the tip of Magoon's Point. About the only thing the railway didn't own was the lake itself, though it would have liked to and may have even tried!

As for the Park, it was used primarily as a picnic area for guests of the Mountain House that was situated directly across the lake. Also, the Lady of the Lake would stop on its routine trips up and down the lake, giving passengers an opportunity to absorb some of the beauty of the surrounding countryside. The railroad even went so far as to sponsor professional entertainment at the Park as William Bullock recorded in the following passage from his book "Bayview Park, that picturesque section just opposite Owl's Head, on the shores of Magoon's Point, used to be the meeting place, for many a joyous company. A large pavilion was located there, in which the Boston Opera Company staged the popular comic operas of the day. They would hold matinees there and evening performances at Newport, going back and forth on the Lady of the Lake. This arrangement was conducted several seasons. It was there I first saw 'Pinafore' 'The Pirates of Penzance', etc." He continues: "Also during the summer band tournaments would be held there, with band organizations gathering from Sherbrooke, Lennoxville, Barton, Lyndonville, St. Johnsbury and Newport. A circus never drew larger crowds. I was so eager to get there that it was no hardship to row a skiff 16 miles for the fun to be gained." Unfortunately, we are uncertain as to the degree to which, if at all, local residents of the Point were able to benefit from the entertainment offered at the Park." Which brings up the whole question of orientation. Was the focus of local residents directed towards the main body of the lake, towards the Park and the tourist trade that flourished around it? Or was the focus directed towards Georgeville or its sister community of Fitch Bay? Despite their own degree of self–sufficiency, the residents of the Point were forced to turn to the outside world on a continuous basis for staples and luxuries that were not available locally. At the risk of offending some of you, I find it necessary to suggest that Georgeville was not the 'center of the universe' back in the 1800s any more than it is today. Though the residents of Magoon's Point were an independent lot, and they opted on many occasions to exploit the resources available in various neighbouring communities from Magog to Newport, all indications are, however, that most trade was directed towards the village of Fitch Bay. This may be puzzling for some of you, but you must realize that the village of Fitch Bay was a dominant political, religious, commercial and industrial center during the late 1800s. It offered far more services for the local farming community than Georgeville could at this point in time, including the option of a variety of denominations for religious services, a number of mills for lumbering and the grinding of grain, and a bevy of artisans and the largest general store this side of Rock Island which collectively provided all the wares one could possibly imagine. Added to this scenario was the topography of the landscape on Magoon's Point, which with its gradual incline to the east, favored access to and from this direction. This particular orientation was also attractive from the standpoint of railway connections, where at Smith's Mills, or what is now Tomifobia, significant railway yards were established to handle both passenger and freight traffic on the Massawippi Valley Railroad. But unfortunately, all this prosperity came to an end. By the turn of the century, a number of changes came about, external forces for the most part, that resulted in the ultimate decline of the community. First of all, there was the displacement of the lime industry that fell victim to overpowering competition emanating from Lime Ridge, in the township of Dudswell. The Magoon family found that it could not compete with this more northerly operation where the deposits of limestone were significantly larger, the purity of the stone much higher, in the 97 percent range, and the access to railway facilities, only a short distance away. Secondly, the whole focus of the tourist industry changed about this time. Most of the large hotels and related facilities were destroyed by fire and their reconstruction not warranted with the changing recreational patterns coming into play. Instead of public accommodation, many former railway patrons began acquiring property for private, lakeside residences. This increased the value of farm acreage bordering the lake and much of it was taken out of 'profit–oriented' agricultural use. As a consequence, large tracts of land fell under the control of a very limited number of owners. This translated into a displacement of population and contraction of employment opportunities. On a more national level, there was the developing trend towards urbanization and industrialization, which was manifested in the migration of farm populations to urban centers in search of factory jobs. There was the agricultural depression of the early 1920s and the Great Depression of the '30s that even more economically viable communities such as Fitch Bay could not survive. Only the dairy industry remained strong, with butter production increasing year after year, well into the 1920s. But even it fell victim to the economic ravages of the time, as Americans ever fearful of their own productive infrastructure, began restricting imports into the U.S. and finally closed the border altogether in 1930. Looking back, today in 1994, we are left with only the remnants of Magoon's Point. To the casual visitor, there are no visible signs of the community that once prospered down on the bend. For the more adventuresome investigator, there are the old foundations of houses and the school, the overgrown and almost obscured cemetery and limestone quarries, and last but not least, the tumbled down pile of rocks that was once the lime kiln. These historical remnants that characterize the present–day landscape, are all that is left to remind us of the families that once lived and played in the peaceful tranquility that was and is, Magoon's Point. In the early years, there were the Magoons, the Blakes, the Adams, the Drews and the Christies. Later came the Brevoorts, the Hutchins, the Cambers, the Merrills, the Boyntons, the Seybolds, the Atkins, the Macies, the Wilsons, the Johnstons and the McTavishes, to name but a few. It is the individual family members of these families and the ones that I have failed to mention that make up the history of Magoon's Point. I will conclude today with a sampling of anecdotes that really portray the essence of these early inhabitants and the countryside in which they lived: ... the tale of a certain Morrill Magoon who in the 1820s was arrested and imprisoned for forgery and who had the audacity to arrange a forged petition calling for his release, with the falsified names of a number of prominent Georgeville residents ... the tale of Hiram Drew and his daughter who traveled all the way from Cornwall by dog sled in the 1840s to take up residence on the Point where he ran a cooper's shop and small store and where he was known on occasion to entertain local Indians, who took a fancy to Mr. Drew's stew and cornbread ... the tale of 'Still Brook' so named not for its tranquil waterway but the distillery operation that produced ample quantities of whiskey and gin for exportation and more importantly, local consumption ... the tales of countless teams and wagons going through the ice especially in the vicinity of Hell Gate at the mouth of East Bay where the current deceptively weakened the surface ice ... the tale of my great grandmother, who upon taking up residence on Magoon's Point, was so lonely for her former residence in Missisquoi, that my great grandfather was forced to secure some of her favorite trees, Lombardy poplars and willows, to appease her ... the tale of my great grandmother watching out her kitchen window in horror as she saw my great grandfather fall through the ice on his way home from securing supplies in Newport one day, her trauma alleviated when she watched in relief, his own self–rescue with the aid of a pocket knife.. the tale of the College farm, upon donation to Bishop's College School, the revenues of which, were awarded in the form of a scholarship for the best essay submitted, and finally, but not least, the tale of Carl Blake's ram who escaped his enclosure one day and proceeded to trap a number of children in the school's outhouse for quite some time before their absence was duly noticed and the errant beast corralled. It is anecdotes such as this that help make history come alive, to give it a human element that is so often lacking. These tales and the facts and figures that I have discussed this afternoon are merely an overview of the history of Magoon's Point. I hope that they have given you some insight into the vitality and character of this one–time community. |

The theme for this year's annual general meeting of the Historical Society is the one–time community of Magoon's Point.

The theme for this year's annual general meeting of the Historical Society is the one–time community of Magoon's Point.