|

Georgeville Historical Society / Societé d'histoire de Georgeville

|

|||||||||||

|

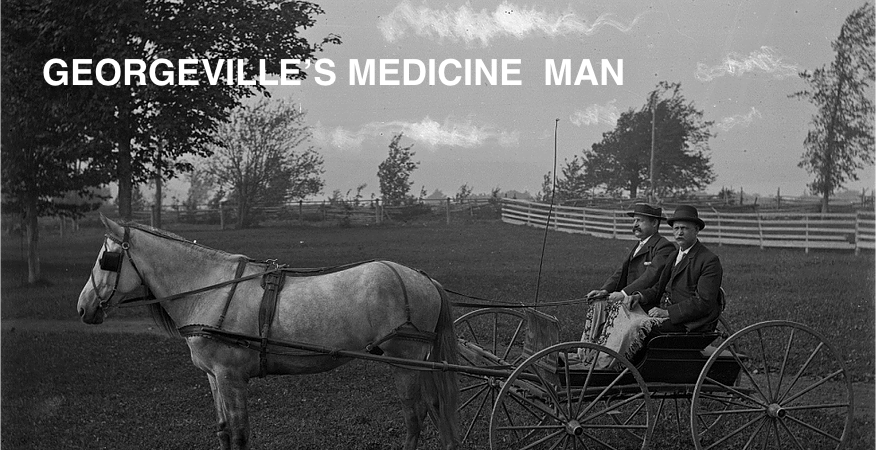

William McKendrick Keyes was just 22 years old when he arrived in Georgeville in 1863, freshly anointed as an M.D. He was born in Bennington, in southern Vermont, one of seven children of a blacksmith, Joseph Keyes, and his wife Eunice Jewett. She must have been a distant cousin of the Jewett families who settled on the lakeshore in the early days of the 19th century and gave their name to Jewett's Point. However, it is another connection that probably explains why the young Dr. Keyes chose to begin his career in Georgeville. Our first record of his presence in the village comes from the Stanstead Journal in April 1863: "W.M. Keyes, M.D. is associated with Dr. N. Cheney in the Reform Practice of Medicine in Georgeville." Dr. Cheney – Nelson Cheney -- was a fellow Vermonter. He had been practicing in Georgeville for three years and was ready to move on. As a reform doctor, he practiced what was known as "kindly medicine", as opposed to the severe blood-letting favoured by mainstream physicians. The reformers, or eclectics, as they were called, were inspired by the observation and use of medicinal plants employed by native American Indians. It is possible that, in search of a successor, Dr. Cheney reached out to his alma mater, the Physio-Medical College of Cincinnati, an important center of the reform movement, and was put in touch with the newly-graduated Dr. William Keyes. If so, this would tell us where Keyes received his medical education. Given his age, it could hardly, by modern standards, have been extensive. But what a career would spring from this beginning! Over the next 51 years, as Georgeville's longest-serving resident doctor, Keyes was not only a revered physician and surgeon. He was also a dentist and pharmacist and manufacturer of patent medicines, a Justice of the Peace and postmaster, a grain merchant, grocer, and stationer, and the proprietor of one of Georgeville's largest and most popular summer boarding houses. And, yes -- there's no avoiding it – in an era of strict liquor regulation, he was, in the eyes of some, the village bootlegger. Morris Wilcox, a Georgeville farm boy when the good doctor was in his prime, wrote the following reminiscence of the man who found time for all of these occupations: "Dr. Keyes was a most un-doctorish doctor with his rumpled clothes, vest buttoned askew and his glass eye that always looked straight ahead and bored into you like a gimlet. But, God love his spirit, he would answer a call of distress in any weather and at any distance and his fees were minuscule compared with those of today's specialists -- five dollars for child-birth, twenty-five cents for lancing a boil or pulling a tooth -- fourteen cents for a vial of aconite -- nine cents for a plaster. He had remedies for every known and imagined ill from barnyard bowels to scarlet fever, from Spiritual diarrhoea to smallpox, even a remedy for Old Maid Miseries. Each summer he sent hawkers out on the road peddling his elixirs… Doctors don't come cut to his pattern any more, more's the pity." At this point we have a treat for you. The Georgeville farmer-photographer Newton Brookhouse was a contemporary of Keyes. At the archives of the Eastern Townships Resource Centre at Bishops University, there is a collection of more than 300 Brookhouse photos of people and places, most of them unidentified. John Scott suggested to Jody Robinson, the ETRC archivist, that surely, if there is any justice in this world, one would turn out to be to be of Dr. Keyes. Jody set to work on the problem and Voila! In the photograph below, you are the first to see this remarkable likeness, one hundred years after Keyes' death.

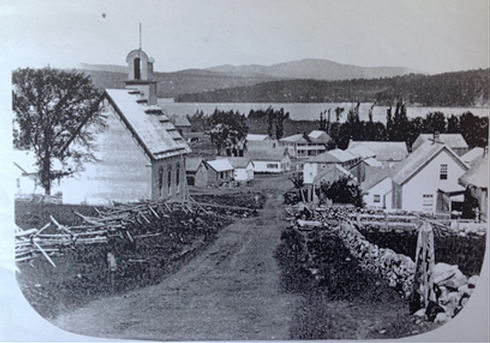

Here the good doctor is holding the reins, posing in his buggy with his brother Samuel, who was a regular visitor from Vermont. The brothers look so much alike they could be twins. Morris Wilcox described the doctor as wearing rumpled clothes, his vest askew. Here he is natty indeed. We believe the photo was taken on the Brookhouse farm north of the village. One detail that leaps off the page in Morris Wilcox's affectionate account of the doctor is the reference to his glass eye. From this distance we can't say how Dr. Keyes lost an eye. But it's worth remembering his father's occupation as a blacksmith. Injuries from flying embers and red hot steel slivers were common. Until I read Morris Wilcox's comments, I wondered how it came about that the young doctor was not caught up in the American Civil War, which raged from 1861 to 1865. Doctors were surely needed. The answer may be that he was unacceptable because of his eyesight. One year after Dr. Keyes' arrival in Georgeville, Dr. Cheney turned the practice over to him and moved to Beebe Plain. There is nothing quite like the thrill of rummaging in the archives and discovering more than you expect. So, it was for me at the Stanstead Historical Society when John Scott, Rev Doreen Keet and I turned the pages of Dr. Keyes' account book for 1864 and found ourselves looking at the page you see below. Along with these purchases Keyes bought, in May 1864, Cheney's house – a no frills, one and a half story frame structure that served as the house and office for three Georgeville doctors in a row – Dr. Martin Luther Scott, who built it in 1858, then Dr. Cheney and now Dr. Keyes. So we call it "the Doctors' House." The house was on the lot now occupied by the Post Box shelter, as you can clearly see in the following photo looking down Channel hill. Deeds describe the property as fronting 40 feet "on the Queen's highway to the steamboat warf.

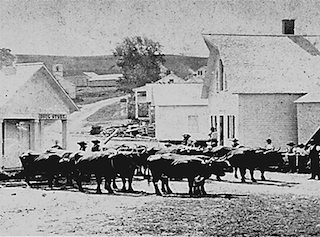

In those days the Stanstead Journal sometimes referred to the South road of Carre Copp as "Dock Street" – that's D-O-C-K Street because it led to the wharf. But it could equally well have been "Doc Street", spelled D-O-C, given the medical activity that occurred in what is now the parking lot. I say this because, next door to the doctors' house and office, Dr. Cheney erected a second building that became his drug store. In the next photo, a truly remarkable image, you see Dr. Cheney's drug store, clearly so marked, on the move in 1864. Dr. Keyes was unable to buy it because Cheney had accepted an offer for it from Thomas Macduff, the Montreal businessman who in 1860 acquired Abraham Channel's old Tavern Stand (which he renamed the Camperdown).

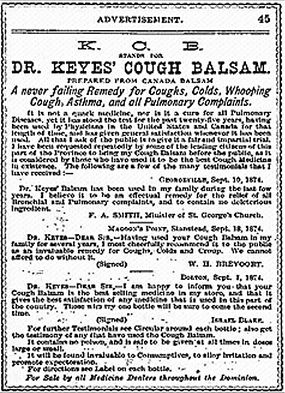

Here, watched by a gathering of men and boys in straw hats, a dozen oxen are towing the building to Wigwam Point. It became the Macduff family's summer home and survived until just a few years ago. Unfortunately, some of the detail in this rare photo is now washed out, though you can make out the Bullock store, then the doctors' house, and the red school house in the background. Many people treasured favourite stories of William Keyes. Emma Woodard, a daughter of the blacksmith and cooper, Benjamin Woodard, told what she had heard of her father's birth in 1868: "Good old Doctor Keyes. He drove by team up to the top of Bunker Hill and delivered my Dad (12 lbs.) and took his pay in coopering". Coopers made wooden barrels. In what was still frequently a barter economy, Keyes was often paid in butter or beef or other farm produce. Adeline Tuck, a daughter of Edmund Tuck, who drove the stage coach between Georgeville and Magog, described the doctor as (quote) "a good friend always. So many miles he drove in a rickety buggy with his cheerful 'Come SKEEB along' to his tired old horses. One could not be rested from a trip 'under Bunker' or over to Bolton before the dear doctor (who never admitted he was tired) started off in some other direction, then changed horses, and started all over again." Mabel Barrows, whose family camped at Birch Bay and Cedar Lodge, remembered when she was a little girl, and Dr. Keyes allowed her accompany him on his rounds, covering sixty or seventy miles in a day. At one point the Journal's Georgeville correspondent wondered in print if the doctor's horses could keep up with his pace: "Dr Keyes had his horse drop dead in the road last Thursday while returning from visiting patients at Fitch Bay. If the doctor had as many horses as he has lost by sickness, accident and drowning since he came here, he would have a large drove." Now we come to the stuff of romance. Our young doctor lost no time before courting one of the village's fair young ladies, Susan Emeline Packard. Her parents were Chester B. Packard and Anna Mills Copp, whose own marriage joined two of Georgeville's founding families. On May 15, 1864, just three days after he bought the doctors' house, Keyes married the girl he would carry over its threshold. The Rev. James Thorneloe, himself newly arrived in the village, officiated at their wedding in the Methodist church. In 1867 the couple welcomed their first child, daughter Anna. The young family joined in the pleasant routines of village life, and Dr. Keyes threw himself into his work with unending energy. He presided over the Dominion Day celebrations in Georgeville in 1870 that were marked by the ringing of bells, displays of flags and fireworks. He became a founding officer of the Masonic lodge established in 1873. He switched his church allegiance from Methodist to Anglican and became a warden at St. George's. Then disaster struck, of a kind Keyes was familiar with as a doctor, and was powerless to prevent. On March 4, 1874 their son, William, was born, but the birth was complicated. A week later, his wife Susan died, aged 30. Grief was compounded four months later when William died as well. Dr. Keyes sought to avoid the pain of grief by doubling down on his workload, a common survival technique. He had earlier made a modest start in the patent medicine business by launching an elixir of his own. The following ad gives you an idea of the world of make-believe occupied by patent medicines of the day.

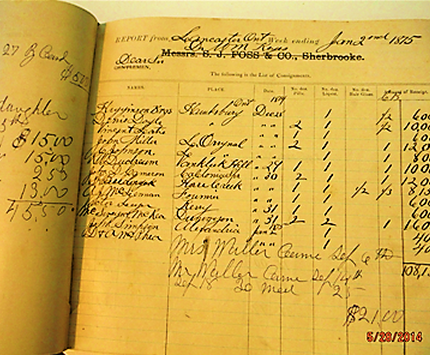

As you see, it claimed that his Cough Balsam was "a never failing remedy for Coughs, Colds, Whooping Cough, Asthma, and all Pulmonary Complaints. It can be given at all times, in doses large or small." It claimed to be available throughout the country and to have been on the market for 25 years. That would have meant, if you thought about it, that Keyes had devised his Cough Balsam at the age of nine. Patent medicines were generally dressed up with such claims to help keep the law at bay. That was just a beginning. In July 1874 the Stanstead Journal reported: "Dr. Keyes has bought of S.J. Foss of Sherbrooke his stock and trade in Dr. Colby's Tonic Pills, Jacobs Rheumatic Liquid and Hunt's Empire Hair Gloss, and will continue to manufacture the same at Georgeville in connection with his Cough Balsam." Dr. Moses French Colby, who died in 1863, the year Keyes arrived in Georgeville, was one of the subjects in the Stanstead Historical Society's fascinating exhibition at the Colby Curtis Museum. His Anti-Costive and Tonic Pills were advertised as "a safe and reliable remedy in all diseases of Stomach, Liver and Bowels. They are no Quack Medicine puffed up by high sounding testimonials from imaginary people, but are the result of forty years of experience of a first-class physician. Jacob's Rheumatic Liquids virtually guaranteed to keep you in glowing good health from cradle to grave. It promised (quote) "immediate relief and permanent cure of Rheumatism, Sprains, Bruises, Burns, Frost-Bites, Lame Back, Side, Limbs or Stomach, Cramp, Numbness of Limbs, Swelling of Joints. Sudden Colds, Diptheria, Sore Throat…It is invaluable to persons predisposed to Paralysis, or subject to attacks of Heart Disease". I noted earlier that Dr. Keyes switched his allegiance from the Methodists to the Anglicans and I think I know the reason why. The whole point of patent medicines, which rarely were patented, was that they were composed mostly of alcohol, with a flavouring of distilled plant oils. For all the extravagant claims of the ads, people knew what they were buying, and buy it they did. One of the village notables who endorsed Keyes' Cough Balsam was the Rev. F.A. Smith, the rector of St. George's from 1870 to 1876. The Methodists, however, must have hyperventilated. They have a long history of condemning the sale and use of alcohol, in any form, and certainly the abuse of alcohol was a serious social problem. On the other hand, in defence of Dr. Keyes, his was an era when the everyday pain medications we use today had yet to be invented, and alcohol was a common remedy. Brevoort, an ancestor of Stephen Moore and several other Atkin families, said of Keyes' Cough Balsam: "We cannot afford to do with I note that at least one strong Methodist, W.H. out it." My first impression was that Keyes simply marketed his medicines from the back of his buggy. But that considerably underestimated his business acumen. This page from one of his ledgers shows that he took over a supply of unused account books from Sherbrooke's S.J. Foss & Co.

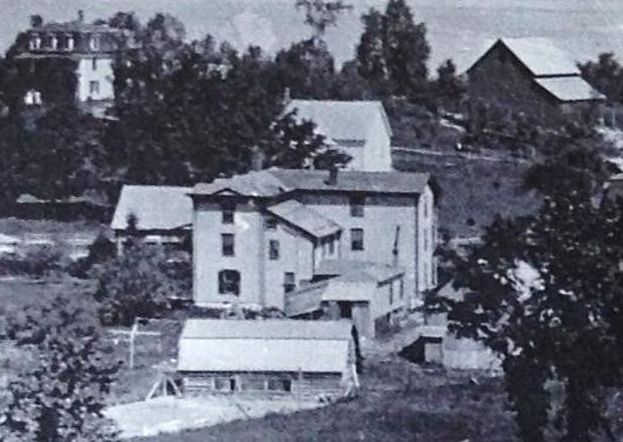

The ledger gives us a list of storekeepers throughout the Townships who carried his goods, headed by Georgeville's William McGowan, Jr. Others were in East Bolton, Stanstead Plain, Magog, Sherbrooke, Waterville, Compton and so on. But his reach was further than that. There is evidence that he signed up storekeepers in such Ontario towns as Lancaster, Hawksbury and Vankleek Hill as shown in the following photograph. Keyes enjoyed a trouble-free 33-year run as a distiller until a winter day in 1896 when an Inland Revenue officer raided his distillery and carried away the works. Summoned to court in Sherbrooke, he pleaded guilty to running an illegal still and was fined $250 – a significant sum, the equivalent of $7,000 today. Where was the distillery? In its coverage of the Great Fire of Georgeville in July 1898, the Journal noted that sparks from the burning buildings in the heart of the village set aflame the shed that had housed the distillery. It was on Chemin McGowan, just above the Desbarats house, and equipped with an excellent spring that until recently served the Murray Memorial Centre. At the time of the fire, the distillery had been repurposed (as is said today) to a more modest function – it was a shed for storing hay. Dr. Keyes never resumed manufacturing medicines. But along the way he considerably improved his office and living quarters. In 1878, a new owner of the Camperdown, William E.L. Tuck, was anxious to be rid of the doctors' house in order to improve the view of the lake from the hotel. So he offered Keyes a trade – in return for the doctors' house plot he would give Keyes a fine building lot on the South road of Carre Copp. The building lot was where the Wee House is today. In 1878 it was on the lake side of the new, thee-storey Masonic Hall, built in 1873 by Nathan Beach. Keyes decided to build afresh, and work started on what would become the first wing of his summer boarding house, Lake Hall. By October the Journal reported: "Hammers are nearly done sounding on the Doctor's establishment, and the plasterers are aching to lay on." Dr. Keyes and his daughter, Anna, were able to move into their new quarters in time for Annna's 12th birthday in January of 1879. He was soon able to rent space in the Masonic building next door for his drug store. His energy unflagging, he eventually expanded the store to include shelves of groceries and stationery supplies as well as his medicines. While he was at it, he also became the village Post Master.

It was characteristic of Keyes that he provided space for the Georgeville Public Library. The librarian was his assistant Post Master, a young lady named Lillian Arthur. Mabel Barrows gives us a good account of the library in a letter from Cedar Lodge to her parents who were travelling in Europe: (quote): "It was the thing of the season -- and you weren't here. You may not have got a very full account of it in the London papers so I will describe it. To begin with, it was for the Georgeville Public Library, and the tickets were sold at twenty-five cents apiece... The audience, who numbered over 125, came from Georgeville, Newport, Magog, Perkins' Landing, Fitch Bay, Knowlton's [Landing] and all around. After the steam launches and rowboats arrived, there were [skits, songs and recitations]… People were delighted …and there was a pleasantly virtuous feeling that they were helping the library. And it did help, for we made $25. We are going to give Miss Arthur something now. Next summer, I think we ought to be able to get a little building for it in the village. We must try, anyway." If his trouble with the revenuers brought Keyes some unpleasant publicity, another set back fortunately went without notice. At a private meeting, a board of the Quebec College of Physicians and Surgeons decided that eclectic doctors were not up to snuff, and Keyes was denied a licence. There was no public announcement of the decision. It did not stop the provincial authorities from asking him to spend days vaccinating people against smallpox. Still, the rebuff must have cut him to the core. He also could not avoid sorrow and sadness. In 1897 daughter Annie died of pneumonia, aged just 27. Her obituary in the Journal described her as "a very estimable young woman who had been the hope of her father's life for many years." A few months later, Keyes addressed his loneliness by marrying Nellie Willard of Bolton Center. She died in 1911. In his last major business venture, in 1889, Dr. Keyes added a three-storey wing to Lake Hall. The new wing faced the lake allowing him to put up as many as 40 summer boarders. It was convenient because Dr. Keyes' store was just next door in the Masonic Hall. The photographs on this page gives you a fascinating view of the view of Georgeville waterfront as passengers arriving on the Lady of the Lake would have seen it in the summer of 1893, the year before Charles McGowan added the 3rd storey to the Auberge McGowan. Lake Hall is, of course, to the right. Lake Hall was fortunately empty when it burned to the ground in December 1912. The aging doctor then bought and moved into the Masonic building, which was known as the Keyes Block until it was torn down in the 1930s. Some of our older residents remember it as an abandoned and derelict structure, with some of the doctor's record books scattered around on the dusty floor. Thanks to some public-spirited citizens, four of his oldest ledgers were rescued and are now in the Stanstead Historical Society archives. Some years ago John Scott found two more and they are in our archives. I began by quoting from a memoir by Morris Wilcox, the farm boy whose parents, Willis Charles and Mary Frances Wilcox, looked after the Barrows family and its camps at Birch Bay and Cedar Lodge. In closing, I turn to a time of crisis in the Wilcox family, one that demonstrated the great respect that Isabel Barrows had for Dr. Keyes. The episode is worth noting because Isabel undoubtedly had a more intensive medical education, the Women's Medical College in New York and a term at the Univesity of Vienna, than did Dr. Keyes. In 1898 Mary Francis Wilcox nearly died in labour. Isabel wrote to her husband, Samuel June Barrows, in Boston: "I spent the night with Mrs. Wilcox. She had a fairly restful night, taking morphine. Dr. Keyes thinks with good nursing she will pull through, but she has been very sick. We buried the little baby just before sunset. It was a beautiful boy, large and sturdy." To Isabel's account, the St. George's register adds a further note: "Surviving but a few moments, [the baby] was baptized by Dr. Keyes." Dr. Keyes himself died, at age 73, on June 28, 1914, one hundred years ago. He was a good and caring man who for half a century gave much of himself to the people of this community and countryside. |